This blog provides some detail on why we use lateral trunk supports, how they can be configured to provide a clinically appropriate solution, and an overview of the range of lateral trunk supports available from Spex to enable the correction of postural asymmetry.

Even after we have correctly supported and stabilised the pelvis in sitting, the trunk may require additional support to withstand the effects of gravity, reduce fatigue and effort of sitting, and maintain an optimal position to support arm use and freedom of movement at the head and neck. Postural asymmetry requires reinforced support and stability – the trunk is no different. The spinal column and musculature are what hold our trunk upright above our pelvis against gravity. The spine transfers the load from the head and trunk to the pelvis and allows movement in the sagittal plane (flexion and extension), frontal/coronal plane (abduction and adduction) and transverse plane (rotation). The spinal column alignment can change due to neurological conditions and/or trauma.

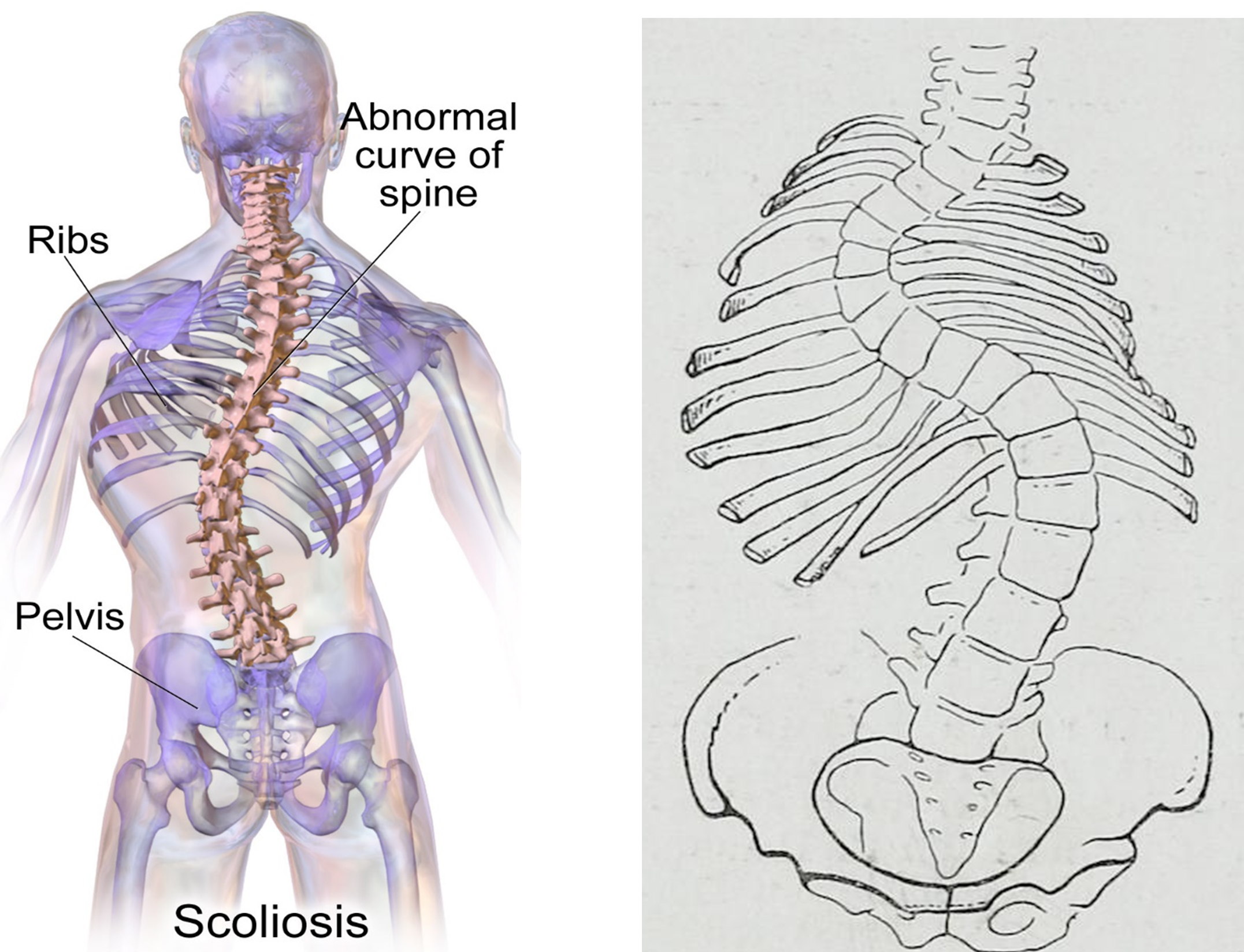

Image Source: Wikipedia

Image Source: Wikipedia

One common condition that affects this alignment of the spinal column is scoliosis, which can occur at any age and be linked to congenital, neurological or idiopathic (unknown) origins. To an observer, a person with scoliosis may present with uneven shoulders, uneven shoulder blades (scapulae), uneven pelvis (with one side lower than the other, known as pelvic obliquity) and a rotated or side-ways bend in the spine. The sideways curves that are created – these can be either a C or S-shape – lead to changes in muscular activity and orthopaedic alignment. Posture becomes less efficient and more effortful. When we think about the planes of movement you might see:

| Coronal/Frontal Plane | Lateral trunk flexion (sideways bend) |

| Transverse Plane | Rotation/twisting of the vertebrae or pelvis. |

| Sagittal Plane | Hyper-/hypokyphosis (severe or flattened thoracic spinal curve) Hyper-/hypolordosis (severe or flattened lordotic spinal curve) Flat back (spinal curves absent or significantly reduced) |

Scoliosis affects the symmetry between left and right sides of the trunk and can add to exaggerated lumbar or thoracic curves.

When any of this asymmetry is present, it can change where the back contacts the wheelchair back support. This, in turn, affects weight distribution and stability, which is why lateral trunk supports may be required for additional support in the seated position.

“While, according to Newton’s Law of Gravity, we can predict where the apple that falls from a tree will land, we cannot similarly predict where a leaf that falls from a tree will land. The tree leaf falls according to the same laws, but the precise location of its landing remains unpredictable because the leaf is more sensitive to the wind. This type of unpredictability also defines the development and progression of scoliosis in an individual.”

(Berdishevsky et al., 2016)

Scoliosis can also be influenced by the alignment of the pelvis (see below). In the presence of pelvic obliquity, the spine and trunk muscles will need to adjust and respond to maintain stability. When a wheelchair user has weakened muscles or fatigue, this can exaggerate the instability they experience in sitting with an increased likelihood that they will begin to lean to the side or need to prop on their arms in order to maintain equilibrium. Therefore, we need to ensure the pelvis is as symmetrical (level/neutral) as possible to eliminate secondary trunk and spine asymmetries in sitting.

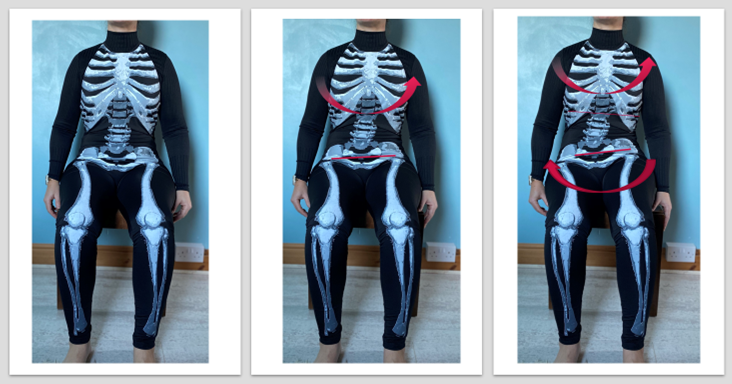

Our bodies will naturally adapt and respond to pelvic asymmetry. Figure 1 and Figure 2 are examples of how my body responded to the increased instability caused by a pelvic obliquity. The type of lateral trunk support selected depends on the presenting postural asymmetry and functional need. If you try to copy the postures above, you will feel how effortful sitting becomes. This can cause fatigue, create pain or increased pressure to weight-bearing surfaces, reduce sitting tolerance and lead to awkward posturing during engagement in activities as the body tries not to fall over. Wheelchair prescribers seek to optimise pelvic (and other body segment) alignment and reduce the effort of sitting so that wheelchair users are physically able to engage in their activities and function whilst seated in the wheelchair.

Lateral trunk supports can help reinforce support when there is asymmetry by:

- Reducing the severity of leaning to the side by supporting the trunk (in the case of a reducible asymmetry) by optimising alignment.

- Blocking the direction of undesirable movement to reduce secondary postural deformity.

- Providing additional support to the trunk against gravity to reduce the effort of sitting.

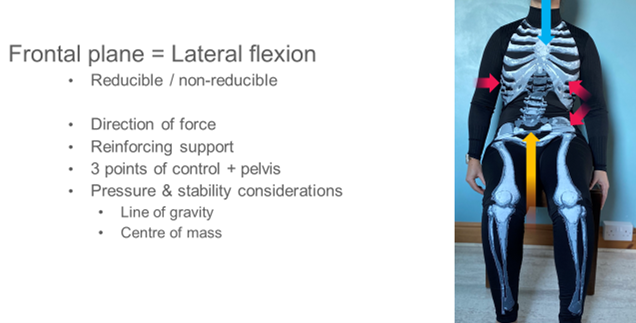

You may have heard clinicians talk about 3-points of control, which simply refers to the biomechanical response to a c-shaped curve where supports are placed to prevent the curve from getting any worse. The curve is blocked at the ends of the curve and at the apex of the curve. By applying force, the C-shape may be reduced. Using this principle, we use lateral supports to support and/or reduce spinal curves to prevent the C-shape from increasing. This is illustrated in the figure below.

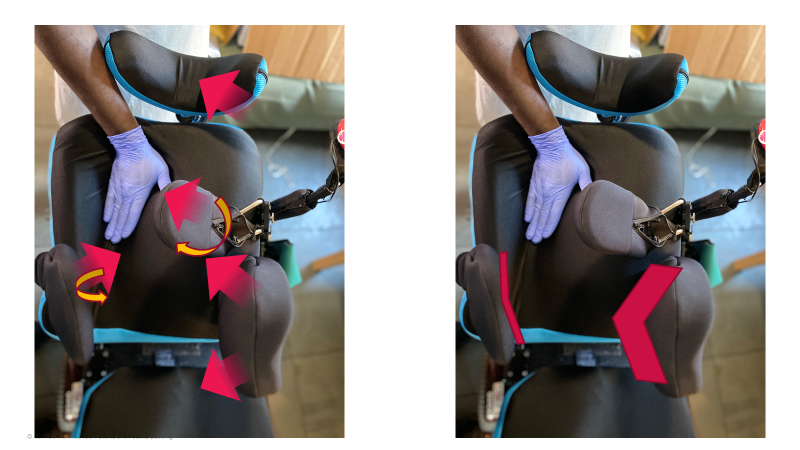

Here I demonstrate how lateral trunk supports can be used to provide three points of control (red arrows) to respond to the spinal curve to the left. Key to remember is that the pelvis must also be stabilised. The blue line indicates the line of gravity that is a constant force on the body pressing vertically down. The yellow line indicates the reactive force performed by the cushion or seating surface. We need to consider the body’s centre of mass – the point at which the all the forces are applied and equilibrium has occurred. Equilibrium may be unachievable for some wheelchair users where muscles and alignment make it too effortful to maintain without posterior (back) or lateral (side) support.

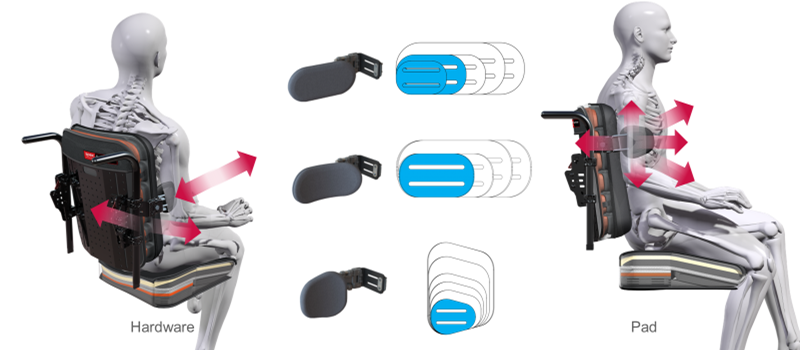

An active user may require lateral support for stability and orientation of the trunk whilst they self-propel the wheelchair. The lateral supports may need to be easily removable for ease of transfers (such as swing-away mechanisms) and may allow the wheelchair user to easily move forwards from the back support for functional activities without restrictions (such as with flat lateral trunk support pads that do not curve around the trunk). A prop-sitter, someone who requires propping on their hand(s) to maintain sitting balance, may require lateral supports for stability and reinforced support due to muscle weakness, scoliosis or trunk rotation to be able to use their hand(s) for function. Support pads may need to be curved to better distribute pressure and meet the contours of the body. Some wheelchair users cannot use their arms to support themselves. They would require lateral supports for reasons explained above and to ensure that the body is sufficiently supported against gravity to allow them to sit without collapsing. Support pads and hardware may need to be able to respond to more complex positions against the trunk to provide stability and comfort.

Examples of Spex hardware to ensure that the lateral support pad is able to reach the wheelchair user’s body in the correct position. These include straight, off-set, cane-mounted, extended and reinforced options to meet particular user needs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Examples of Spex pad sizes and adjustments possible within the Spex hardware and pad combinations.

An example of how the Spex swing-away laterals can provide posterior-lateral or lateral-anterior support to respond to unique trunk asymmetry and shaping (left & centre), and how the axial technology allows pads to be angled upwards or downwards to support the lateral contours of the wheelchair user’s body (right).

Example of Spex modular lateral trunk supports for a wheelchair user with severe scoliosis. Including: new biangular lateral trunk supports, narrow contoured lateral support, axial hardware and the ability to offer multiple points of control and support for the trunk, in addition to the lateral axial hip/thigh supports and headrest for support at the pelvis and head, respectively.

- Ágústsson, A., Sveinsson, Þ., & Rodby-Bousquet, E. (2017). The effect of asymmetrical limited hip flexion on seating posture, scoliosis and windswept hip distortion. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 71, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.09.019

- Berdishevsky, H., Lebel, V. A., Bettany-Saltikov, J., Rigo, M., Lebel, A., Hennes, A., Romano, M., Białek, M., M’hango, A., Betts, T., de Mauroy, J. C., & Durmala, J. (2016). Physiotherapy scoliosis-specific exercises – a comprehensive review of seven major schools. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-016-0076-9

- Costigan, F. A., & Light, J. (2011). Functional Seating for School-Age Children With Cerebral Palsy: An Evidence-Based Tutorial. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2010/10-0001)

- Johnson, S. (2019, August 2). Everything You Need to Know About Scoliosis. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/scoliosis

- Konieczny, M. R., Senyurt, H., & Krauspe, R. (2013). Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics, 7(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-012-0457-4

- Lange, M. L., & Minkel, J. L. (2018). Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A clinical resource guide. Slack Incorporated.

- Miller, F. (2018). Early-Onset Scoliosis in Cerebral Palsy. In F. Miller, S. Bachrach, N. Lennon, & M. O’Neil (Eds.), Cerebral Palsy (pp. 1–14). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50592-3_117-1

- Park, W. M., Wang, S., Kim, Y. H., Wood, K. B., Sim, J. A., & Li, G. (2012). Effect of the Intra-Abdominal Pressure and the Center of Segmental Body Mass on the Lumbar Spine Mechanics – A Computational Parametric Study. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 134(1), 11009-NaN. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4005541

- Stokes, I. A. F., Gardner-Morse, M. G., & Henry, S. M. (2010). Intra-abdominal pressure and abdominal wall muscular function: Spinal unloading mechanism. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 25(9), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.06.018

- Waugh, K., & Crane, B. (2013). A clinical application guide to standardized wheelchair seating measure of the body and seating support surfaces. (Revised). Assistive Technology Partners. https://pva-cdnendpoint.azureedge.net/prod/libraries/media/pva/library/publications/lib_waugh-guide-to-seating-v2-measures-revised-ed-compressed.pdf

- Weinstein, S. L., Dolan, L. A., Wright, J. G., & Dobbs, M. B. (2013). Effects of Bracing in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(16), 1512–1521. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1307337

- Weppner, J. L., & Alfano, A. P. (2019). 6—Principles and Components of Spinal Orthoses. In J. B. Webster & D. P. Murphy (Eds.), Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices (Fifth Edition) (pp. 69-89.e2). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-48323-0.00006-8