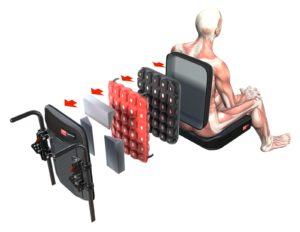

The back support, cushion height and width selection is dependent on a number of factors. The base of the back support generally runs from the height of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) to the chosen height against the user’s back depending on the support needed for stability and the freedom of movement required at the shoulders (e.g. if a wheelchair user is self-propelling).

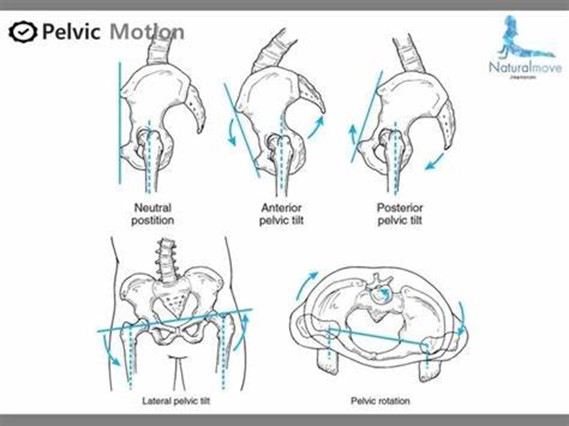

The cushion and back supports are primary surfaces involved in functional seating and both have a direct effect on sitting posture. This is a two-part blog that explores how the back support can offer biomechanical support to maintain pelvic alignment and stability, particularly in the transverse plane (pelvic rotation) and sagittal planes (posterior/anterior pelvic tilt).

How easy have you found it to adjust contouring in the back support to respond to asymmetry in the transverse plane of motion (rotation)?

We will be exploring how back supports can be better contoured to respond to asymmetry in the sagittal plane, namely with pelvic anterior and posterior tilt, in Part 2 of this blog.

Thank you for reading!

- Babinec, M., Cole, E., Crane, B., Dahling, S., Freney, D., Jungbluth-Jermyn, B., Lange, M. L., Pau-Lee, Y.-Y., Olson, D. N., Pedersen, J., Potter, C., Savage, D., & Shea, M. (2015). The Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA) Position on the Application of Wheelchairs, Seating Systems, and Secondary Supports for Positioning Versus Restraint. Assistive Technology, 27(4), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2015.1113802

- Costigan, F. A., & Light, J. (2011). Functional Seating for School-Age Children With Cerebral Palsy: An Evidence-Based Tutorial. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2010/10-0001)

- Kobara, K., Eguchi, A., Watanabe, S., & Shinkoda, K. (2008). The influence of the distance between the backrest of a chair and the position of the pelvis on the maximum pressure on the ischium and estimated shear force. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 3(5), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100802145332

- Minkel, J. L. (2018). Seating and mobility evaluations for person with long-term disabilities: Focusing on the client assessment. In Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A clinical resource guide (pp. 3–26). Slack Incorporated.

- O’Sullivan, S. B., Schmitz, T. J., & Fulk, G. (2019). Physical Rehabilitation (7th ed.). F.A. Davis.

- Samuelsson, K., Bjӧrk, M., Erdugan, A.-M., Hansson, A.-K., & Rustner, B. (2009). The effect of shaped wheelchair cushion and lumbar supports on under-seat pressure, comfort and pelvic rotation. Disability & Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 4(5), 329–336.

- Sprigle, S., Wootten, M., Sawacha, Z., Thielman, G., & Theilman, G. (2003). Relationships among cushion type, backrest height, seated posture, and reach of wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 26(3), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2003.11753690